I aften åbner den britiske film- og videokunstner Emily Wardill i x-rummet på Statens Museum for Kunst i København med en soloudstilling, hvis lange titel stammer fra et essay af W.B. Yeats: «…found himself in a walled garden on the top of a high mountain, and in the middle of it a tree with great birds on the branches, and fruit out of which, if you held a fruit to your ear, came the sound of fighting…»

Det sanselige paradoks (lyden af en slåskamp i en frugt!), som titlen indebærer, er ofte til stede i Wardills værker. Hun trækker på et meget forskelligartet reservoir af viden, genrer og æstetik, der iscenesættes i samme værk. Det så man fx i filmværket Sick Serena and Dregs and Wreck and Wreck (2007), der vistes på Venedigbiennalen 2012. Et skuespil udfoldede sig i et religiøst allegorisk billed-og lydunivers, hvor de udklædte (med store kjoler, parykker og skæg) skuespilleres dialog udtrykte en upassende sort ironi midt i den religiøse sfære – en slags absurd teater, hvor det allegoriske og performative element hele tiden var i centrum.

I den aktuelle udstilling inddrager Wardill neurologien som vidensfelt. Forholdet mellem kroppens bevægelser og sindets erfaringer undersøges i en film, der med kunstnerens egne ord, er en blanding mellem en thriller og et digt. I slutningen af april opførte Wardill performancen For They Know Not på Lilith Performance Studio i Malmö. Performancen, der forløb over to aftener, er forlægget til det filmværk, der vises på Statens Museum for Kunst, og omhandler neurologen Eitienne Motion, der mest betragter kroppen, fx sin underfundige patient, der kun kan røre (på) sig, når han kigger på sine lemmer og aktivt beslutter sig for at flytte dem. Motion har til gengæld glemt at lytte til sanserne og kærligheden. Alt synes besluttet på forhånd, og det instinktive – kroppens reaktion på en pludselig følelse – er ikke mulig. Filmen drejer sig dermed grundlæggende om selvbevidsthed i forhold til vores ageren i verden – men også i forhold til værket i sig selv og vores kropslige erfaring af værkets indhold. Det er denne dobbeltsidighed, den paradoksale sanselighed, der synes at ligge Wardill på sinde.

Emily Wardill er født i Rugby, Storbritannien i 1977, hun er uddannet fra Central Saint Martins College of Art, og har haft soloudstillinger på blandt andet ICA i London (2008), de Appel i Amsterdam (2009) og på Badischer Kunstverein (2012). Dette er hendes første udstilling i Danmark.

Emily Wardill har svaret på Kunstkritikks 10 spørgsmål per email. Vi har valgt at publicere svarene på originalsproget.

How are the preparations for the exhibition at Statens Museum for Kunst going?

Great, I am very excited about the show.

What are we going to see, and what is the exhibition about?

I am making a film, the title of which is “…found himself in a walled garden on the top of a high mountain, and in the middle of it a tree with great birds on the branches, and fruit out of which, if you held a fruit to your ear, came the sound of fighting…” It is a kind of love story following the relationships that a neuroscientist has with his pupils, his main patient, Simon and his lover Slalem.

Your exhibition at SMK works with the notion of the body and the mind: what are your thoughts about the old Cartesian dichotomy of mind /body and the classic phrase “I think therefore I am”?

There are things that our bodies know that are very difficult for our minds to learn. The idea that my body grew itself, for instance, I find astonishing.

Film making is a strange mixture of being reliant on technology (and all the idiosyncrasies that this has developed in its journey from still to moving images), being inherently social (so the minds and bodies are multiple and interdependent), being able to collide different times and locations in a way in which individual bodies and minds cannot and liberating the mind and the body from the construction that is “common sense” through the use of fiction, collage and time travel. It also has the particularity of allowing that you see ideas enacted – put into space, made visible and audible – in a way that, say, writing a paper, does not.

You integrate scientific research in your art projects. What role does theory play in your work and what theorists have inspired you lately?

Sometimes you want to read in order to understand how ideas turn into actuality. Sometimes you want to read mechanically – descriptions of how one process begets another. Recently, the most inspiring thing I have been reading is writing about the work of Charlie Chaplin, because it seems to have that quality of description which, within it, a sort of dissection or breaking down exists, which isn’t “theoretical” but is so helpful in an attempt to understand the 20th century and film making as an obstacle course.

The scientific research that fed into the piece here at SMK came about through an on-going conversation that I have been having with the neuroscientist Israel Rosenfield about his work on proprioperception and a particular case of a man who cannot move his body unless he is looking at it. What that means, is that he has no automatic movement. Every movement that he makes requires looking and thinking. Everything he does is on purpose. He moves like a bad actor would move – “I am going to sit down in a chair” and then they sit down in a chair. This character, through his very presence, makes the body and movement very significant. He makes us question what movement we believe.

How would you describe your working method and your specific approach to the medium of video and film?

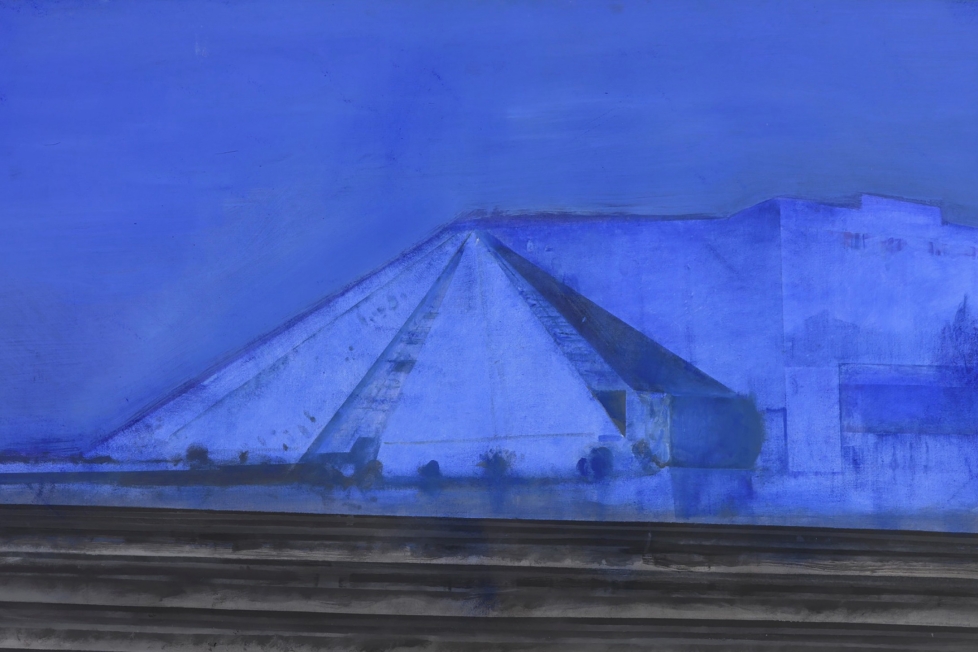

Stylistically, I try to make the way that the work is put together reflect its content without that relationship ossifying. It is important that pieces look different from each other. Having a signature style would work against one of the things that I am interested in – which is when ideas adopt a spatial model and lodge there. Often that spatial model is imaginary, yet pertains to a usefulness, and this, without the dexterity of an acknowledgment of fiction, can be suspicious. So I try and find a style for film making which is relevant to a particular piece. With Game Keepers without Game (2009) – that style was such that people were photographed like objects and objects fluctuated between being status symbols, props or evidence of crime. In Ben (2007) everything is shot in colour on a set built to look as though it is shot in black and white. For the film at SMK – the set is a physiotherapy room – which also becomes an obstacle course. It is lit to look like The Night of the Hunter and this lighting makes the room, the body and the faces of actors more expressive. So an interest in gesture, gestures which are easy to misinterpret, our control over our own bodies, love as an act and acting failing when it becomes too self conscious, are also embedded in the style of the film.

When and why did you become an artist?

When I was a child I always wanted to be a waitress on roller skates. My friend Elle describes me as a failed waitress on roller skates.

Can you mention any current art projects or other practices that inspire you?

Willem Van Aelst’s Still Life of Dead Game and Hunting Weapons is stuck in the front of my notebook with a quote from Tolstoy “All, everything that I understand, I understand only because I love”. The film Margaret by Kenneth Lonergan that finally had a release in the UK last year had a large affect on me, and one that I am still trying to work out.

How do you see your role as an artist today?

We need to work out what needs protecting and what needs breaking apart and this never stops.

How can visual artists make a living and still maintain a critical attitude towards the commercial art market and governmental funding bodies?

People survive in different ways. When we used to do Itchy Park at our townhall in Limehouse, we would put on bands, performances, installations and film screenings, charge people £4 on the door and this would cover our costs. It was good to be self funded, but we were lucky in that we had a huge townhall for a peppercorn rent which we found because Eleanor Brown (who co-founded the studio) got chatted up by a councilor in a local bar who told her about the space. I think that it is very important to retain some perspective on how much money governments actually spend on funding the arts in comparison to, say, defense. Because I think that artists are very good at self criticism and in fighting, and that this can be a small circuit to be travelling around. Of course it is good to be critical, but it is also good that governments fund the arts and that practicing art is a viable option for people other than the very wealthy.

What would you change in the world of art?

Where is this world?