Sidst Lisa Anne Auerbach udstillede i vores del af verden var i 2006 på det 2 kvadratmeter store KBH Kunsthal i København – reelt en tidligere butiksmontre opstillet på Vesterbrogade og udnævt, af Jacob Fabricius, som københavns kunsthal. Dengang bestod udstillingen af 3 sweatre. På hendes soloudstilling på den 2000 m2 store Malmö Konsthall (med samme kunsthalsdirektør), er repertoiret udvidet til 25 sweatre, som de ansatte på kunsthallen vil bære i udstillingsperioden. Sweatrene er strikket efter hønsestrikmetoden, som blev opfundet i 1970erne af Kirsten Hofstätter – en enkel strikkemetode, der var farverig, ekspressiv og potentielt tilgængelig for alle at lære. Det er samtidig en stil og metode der bærer stærke reminiscenser af 70ernes feminisme og kvindekamp med sig. En immanent – og i Auerbachs tilfælde, helt bogstavelig – politisk tråd som ligger i forlængelse af kunstnerens generelle projekt med at politisere hverdagsklæder.

Siden præsidentvalget i 2004, hvor Auerbach strikkede sin første sweater for at støtte John Kerrys kampagne , har sweatre og nederdele været hendes signatur. Sweatrene bliver på den måde afspejlinger af en specifik tids politiske diskussioner og spørgsmål eller personlige kæpheste. Udsagnene kan tage form af spidse og sarkastiske spørgsmål som, fx «9-11 Who?? I thought you said you’d NEVER FORGET.» Eller det kan være mere satiriske slogans som «Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition». I Malmø stammer ikke alle udsagn fra Auerbach selv. Mange af dem er på svensk og kommer fra kunsthallens personale og dermed bliver sweatrene udtryk for tanker om at være borger og menneske netop i dette samfund: «Är friheten större här?» spørges der, eller der konstateres: «Jag prater aldrig med min granne».

Auerbach udgiver også sine egne zines under navnet Saddlesore, senest om hendes boghylde, men ellers handler det også meget om at være cyklist i Los Angeles, som hun også skriver uddybende om på sin blog www.stealthissweater.blogspot.com. Hun er født 1967 i Californien og uddannet ved Art Center College of Design i Californien, oprindeligt indenfor fotografi. Hun har senest haft soloudstillinger på American Philosophical Society Museum, Philadelphia (2010), University of Michigan Art Museum (2009), Printed Matter, New York (2008).

Lisa Anne Auerbach har svaret på Kunstkritikks 10 spørgsmål per email. Vi har valgt at publicere svarene på originalsproget.

You knitted your first sweater during the presidential campaign in 2004 in favor of John Kerry and your exhibition at Malmö Konsthall opens just a few days after the presidential election in the US. Will this influence on what we are going to see at Malmö Konsthall?

Europeans know more about American politics than most Americans, for sure, but since the exhibition opens after the election, it doesn’t have anything specifically to do with the presidential race.

For your exhibition at Malmö Konsthall, you have adopted the local knitting tradition, «Hønsestrik». Was this knitting style familiar to you before? And how has it influenced your work for the exhibition?

I learned about Hönsestrik from Annemor Sundbø and Inger Johanne Rasmussen while visiting Norway last March. Before that time, no one had connected the work I was doing with politically themed knitting with any historical knitting movement. When I found out about Hönsestrik, the connection was so obvious. My research into Hönsestrik didn’t get very far; there is nothing about it in any English-language knitting history book. With this exhibition, I am introducing Hönsestrik to a new generation of sweater wearers and sweater makers. The sweaters I’ve designed for Malmö Konsthall are inspired by Hönsestrik, and some of them use motifs often seen in those 1970’s sweaters, but the new sweaters also have a contemporary sensibility. They are not meant to be retro or nostalgic, but to bring the Hönsestrik aesthetic to the present.

What do you consider the most important aspect of this exhibition?

The connection to Hönsestrik is important, and the fact that the sweaters are alive, being worn by the staff of the Konsthall, is also really central to this exhibition.

Traditionally the needlework of women hasn’t really counted as real art (as have paintings and sculptures). Currently, though, you see younger artists take up traditional embroidery and needlework and knitting as yourself. What is it in traditional crafts work that attracts you as an artist?

I learned to knit when I lost access to a darkroom after graduating from school, where I had mostly worked in photography. Knitting doesn’t take a lot of supplies or infrastructure, and at the time I learned to do it, I had more time than money. I was interested in the way that text could be made into a sweater, and how wearing the sweater over time could change the meaning of the text. Sweaters as a medium is still challenging for a lot of viewers. You can make the shittiest painting on earth and never have to explain why it’s art.

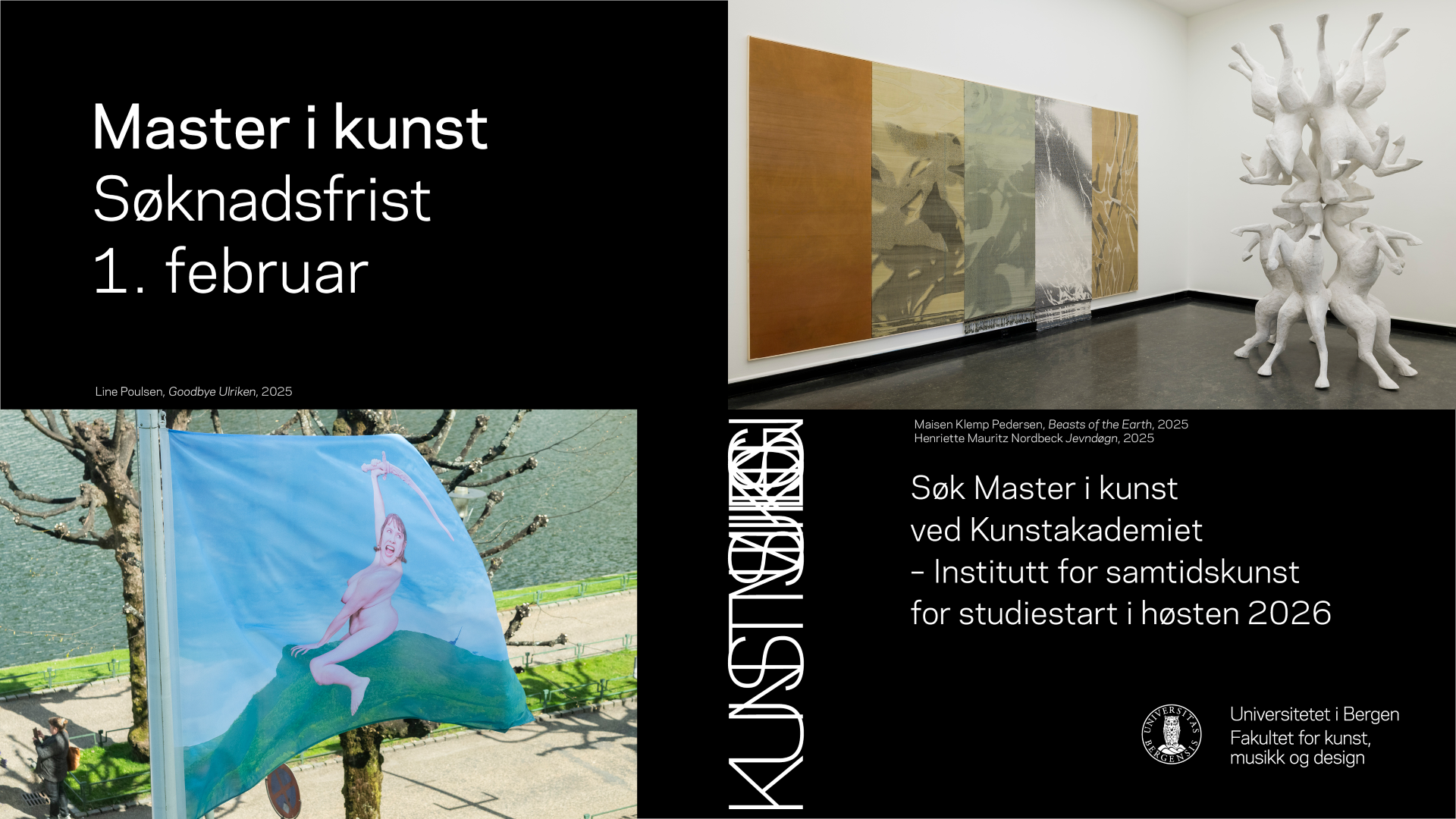

Machine from this Woman?, 2012. Med Marika Bredler. Foto: Lisa Anne Auerbach.

At this year’s Documenta some of the works that really affected me was the large 1930s tapestries by Norwegian artist Hannah Ryggen exhibited in Fridericianum, depicting highly political situations and issues such as the Spanish Civil War and Nazism. Do you consider yourself as part of a certain lineage in this respect?

I love those tapestries, but I didn’t learn about her work until I visited Norway last year. When I saw them at the Kunsthall Oslo, they blew me away. She is an amazing painter with yarn, hand-dying all of her colors and creating gorgeous compositions, allegedly without first making a sketch. Aside from the fact that we both work with wool and have political themes, I don’t feel like my work has much in common with hers. I am not a craftsperson in the same way. For me, the craft is a necessary evil. I want the sweaters I make to exist in the world, and they have to get there somehow, they have to be produced.

What role does humor play in your work?

Humor is really important to my work. I often make sweaters with jokes on them or phrases that are supposed to be funny. The whole enterprise of making sweaters with text on them is ridiculous!

Besides knitting you are also engaged in publications of zines, in a blog about bicycling in LA and in photography (as a teacher). Is there a main thing or theme that connects the various aspects of your artistic productions?

If there had to be one unifying theme, it would probably be narrative. Most of my work tells stories, either through text, sweaters, or photographs.

Can you describe your working method?

My working method changes, depending on what I am working on. When I’m making or designing sweaters, I spend a lot of time sitting at my computer or dealing with a knitting machine. It’s tedious work, and often I am just solving problems, whether they be idea-based or mechanical. Some days I get almost nothing accomplished. Sometimes I just need to clear out my head with a bike ride or at a punching bag. I try to cook almost every night. There’s something about chopping vegetables that I find very productive. If the day feels wasted, it can always be reclaimed with a good meal.

What inspires you the most? And how do you see your role as an artist in connection to this?

The most! This is impossible to answer! A lot of things are inspiring in this world, and as an artist I’m constantly breathing in data and spitting it out in some other kind of form. I find myself sometimes crazy psyched about places I visit or things and people I encounter on my way around the world. Recently while I was visiting my parents, we went to the Garfield Park Conservatory. I had been to places like this as a child, but this time it struck me as absolutely incredible. Suddenly I was in a California landscape, but in a large glass building in Chicago! It just seems so odd and amazing, and I was inexplicably incredibly excited about it. I don’t know how on earth this connects to my role as an artist, but maybe it’s just to say that it’s important to get out of the house. But it’s also inspiring to stay home. My latest small publication, BOOKSHELF, consists of reviews of books I found on my shelves. I am trying to figure out if I really need all those books, so I started looking at them one by one and deciding whether to keep them or not. And this led to a small publication. I’m hoping that people will read this and do the same thing with their shelves. And maybe we can all get together and trade books. Or burn them.

You had a solo exhibition in the tiny KBHs Kunsthal in Copenhagen, 2006. For this exhibition it seems you have had an extensive collaboration with the local environment both with the knitters from Denmark and the staff at the Konsthall that have contributed with some of the wordings for the sweaters. How do you perceive and experience working on exhibition making in this area of the world?

I grew up in Illinois, and there is a large Scandinavian population there, so Scandinavian sweaters have always come to mind when I think about sweaters in general. When I first began knitting, one of the books that really inspired me was Annemor Sundbø’s Everyday Knitting: Treasures from a Ragpile. It made perfect sense that the traditional Norwegian patterns could be constructed to integrate text. I took these patterns as a starting point when I first began making my own. For the KBH Kunsthal, I asked Jacob to introduce me to some local knitting traditions, and he sent me images of a Danish weatherman who always wore custom knitted sweaters. So my small exhibition at that tiny Kunsthal was inspired by the weather and the weatherman and Weather Underground. I feel a little bit like a thief stealing another culture’s knitting traditions, but perhaps sometimes it takes an outsider to animate what the locals perceive as boring and obvious.