Denne helgen åpner Kunstbanken Hedmark Kunstsenter på Hamar en utstilling med nye skulpturer av den ghanesiske kunstneren El Anatsui. Ved åpningen av årets Veneziabiennale mottok han utmerkelsen Gulløven for sitt kunstnerskap, etter anbefaling fra hovedutstillingens kurator Okwui Enwezor. I følge Enwezor er El Anatsui en av de viktigste nålevende afrikanske kunstnerne som fortsatt arbeider på kontinentet. Kuratoren betegnet det å gi ham prisen som «en verdig anerkjennelse av originaliteten i Anatsuis kunstneriske visjon, hans livslange dedikasjon til formell innovasjon, og at han gjennom sitt arbeid har befestet stillingen til Afrikas kunstneriske og kulturelle tradisjoner i internasjonal samtidskunst».

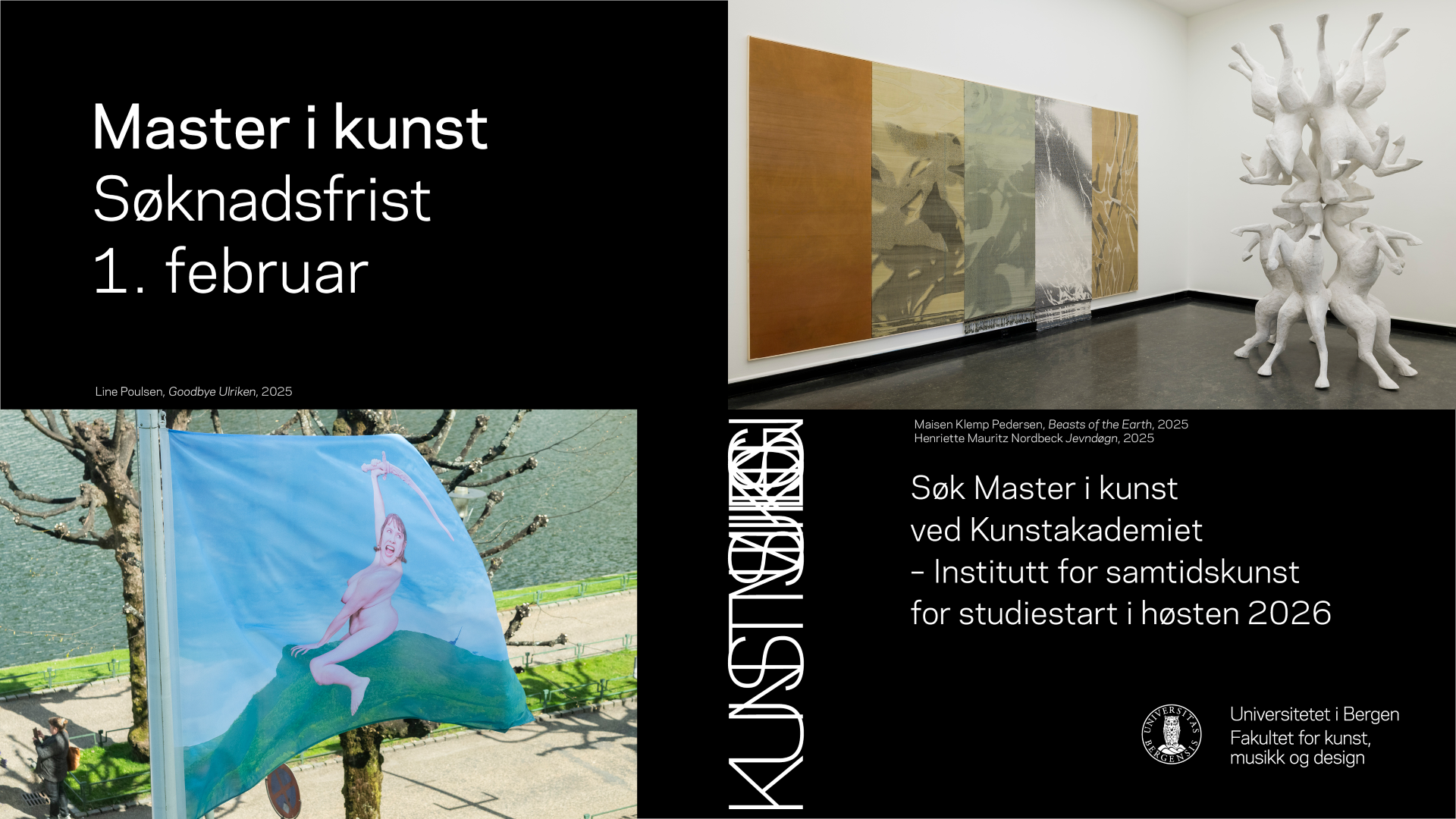

El Anatsui er født og utdannet i Ghana, men bor nå i Nigeria hvor han i mange år var professor i skulptur ved universitetet i Nsukka. Som et av de ledende medlemmene i den såkalte «Nsukka-skolen», ble han presentert på Smithsonian National Museum of African Art i Washington i 1997, men fikk et større internasjonalt gjennombrudd etter at han deltok på Veneziabiennalen i 2007, som del av utstillingen Artempo. Where time becomes art, kuratert av Axel Vervoordt. El Anatsui vekket da oppmerksomhet ved å drapere fasaden til Palazzo Fortuny med en av sine monumentale, skimrende skulpturer laget av flaskekapsler. Det er ikke første gang El Anatsui besøker Norge – i 2008 deltok han i gruppeutstillingen Recycling, også i Kunstbanken på Hamar, hvor han presenterte skulpturen Earth’s Skin på 5 x 8 meter, et verk som senere ble innkjøpt av Guggenheim Abu Dhabi. Det følgende intervjuet ble gjennomført på engelsk, og publiseres her på originalspråket.

First of all: Congratulations! What was it like to receive the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale?

Well, it was a big surprise. I wasn’t expecting it. I always thought that a lifetime achievement award was something you get when you are 80. So it was too sudden, but at the same time it was gratifying because it is a mark of recognition for what I have done in my 71 years. Also, it is an inspiration for me to work harder. Awards lift you up to a point below which you are not expected to perform.

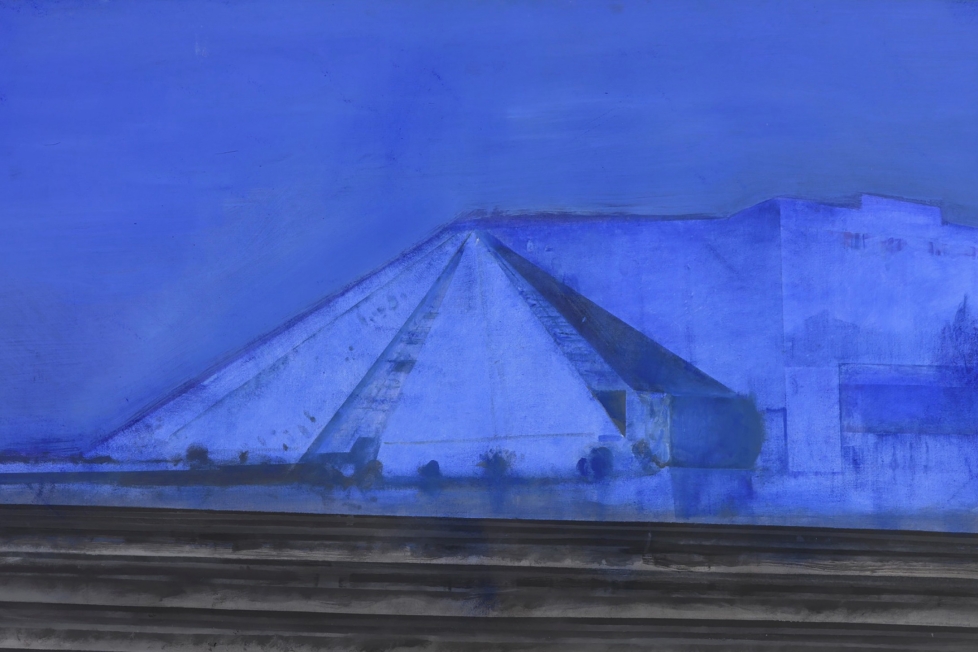

In recent years, you have received international acclaim for your large, even monumental wall sculptures that look a little like abstract modernist carpets or paintings, murals. What are your inspirations?

I have seen so much art, and I cannot pick out something special that has inspired me. For me it is important that the sculptures are free and can take any shape they want. The bottle caps provide the limits of my sculptures. I was not thinking about iconic Ghanaian cloth, but the colours on the bottle caps are the same. I had worked with the bottle caps for a long time before people started talking about Gustav Klimt and comparing my work with his work. When I checked it, I found the relationship was rather superficial. The rectangular forms he used looks like the bottle caps I use, but I think our intentions are different.

You have exhibited in Norway before, also at Kunstbanken, as part of the group show Recycling in 2008. However, I read in an interview that you do not want to label your work as “recycling”, but rather as a transformation. You talk of the artwork reaching a higher dimension. Could you please elaborate on that?

Maybe my inspiration is that it gives more room, more hope to situations one would think of as lost; for instance a bottle cap is not supposed to have any value again, but when I pick them up and use them, they acquire new meaning. Maybe it is like thinking about the fate of people that have no hope and no place to look to. Being given a new lease of life. I give a new and higher status to the bottle caps, and that is not recycling.

What will you be presenting at Kunstbanken this time?

Seven pieces that are still in the bottle cap medium that I have worked in for many years – I originally thought it was going to have a short run as a medium, but it has continued to reveal new possibilities and fresh meanings. The title of the exhibition is dzi, which has many meanings in my language, Ewe, like increase, search, sing, give birth and heart. The fact that this word means so many things gives me the idea that it is like the art itself, and means many different things to different people according to what they bring to it. The work I am presenting at Kunstbanken this time is more of an expansion of the vocabulary I presented here seven years ago.

What are you working on at the moment, besides your show in Hamar?

Well, I am working for the show Atopolis in Mons in Belgium in June and the summer show of the Royal Academy in London. And later in the year I will be at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art somewhere in Japan.

Okwui Enwezor, who recommended you for the Golden Lion, is the first African curator of the Venice Biennale in its 120-year history. What impact do you think Enwezor has had on the international recognition of African art?

I think the impact of Enwezor has been in three ways: He founded the journal Nka, which is about contemporary art in Africa; as a curator he has given visibility to art made by African artists, and he has given African artists opportunities to be shown in a world forum.

Talking of “African art”, I am aware that the term might be considered much too wide to make any sense at all…

The term “African art” is like narrowing or pigeonholing. For a long period what was shown as art was from Western sources, and it wasn’t called European art, it was just called art. The danger of pigeonholing is that it narrows people’s expectations, it limits them to certain preconceptions. They will not look beyond this or even approach works with an open mind. Music is music, art is art, science is science. When I listen to music I am listening to the sound and how the elements relate to each other; I do not necessarily hear it as music from a specific country.

What would you like to change in the art world today?

Categorising.