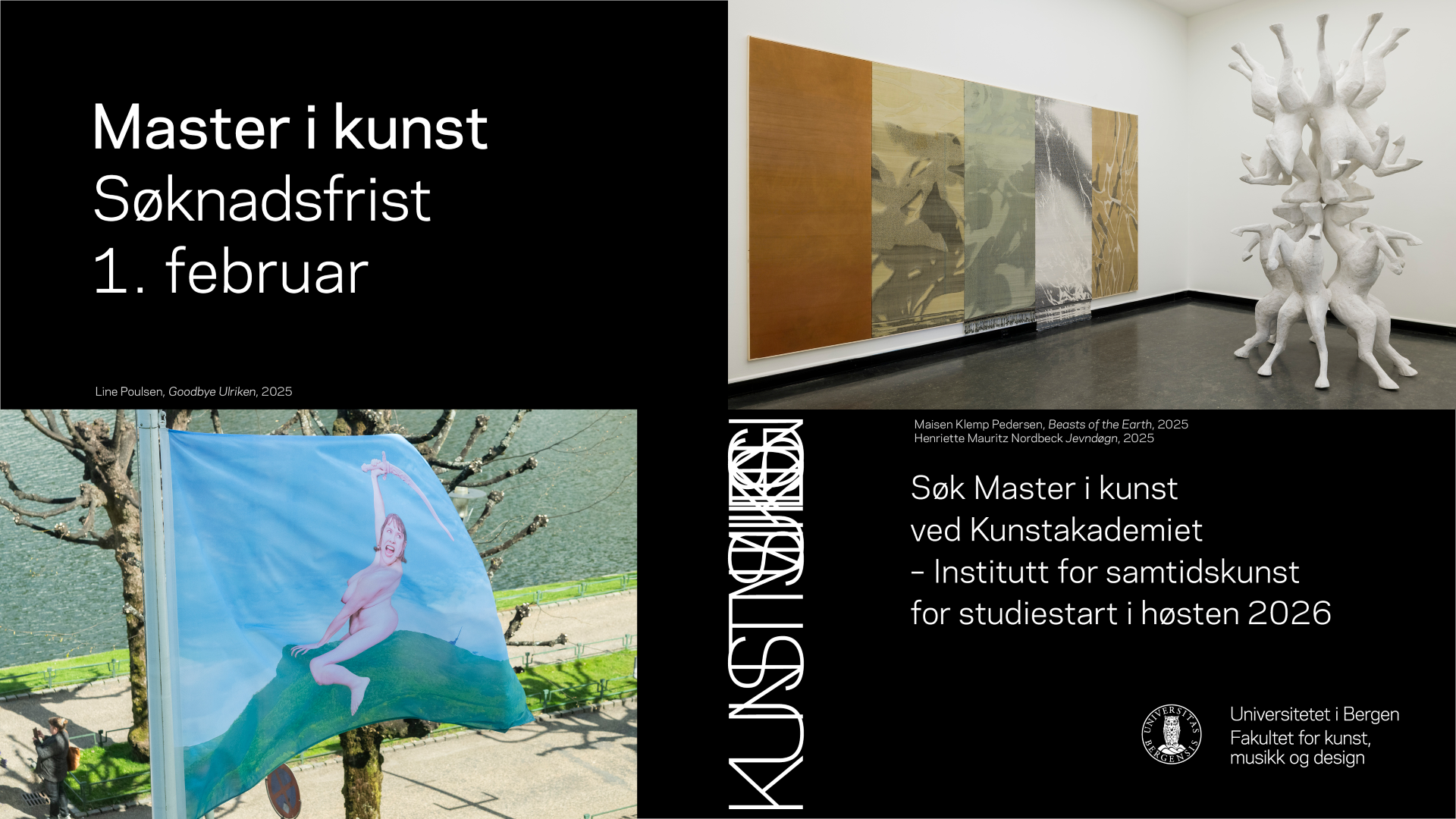

- Gesamt. Disaster 501 – What Happened to Man?, 2012. Film still. Concept by Lars von Trier. Edited by Jenle Hallund.

From Occupy Wall Street to the Arab Spring we are currently seeing a wealth of movements aimed at giving people more power over their civilian, collective destinies. As a result, one of the concepts undergoing the greatest amount of change today is the notion of «authority»: who has the right to decide what others should do? Some believe that this development is mirrored within the world of art. Here, authorial authority is under pressure from a continually expanding phenomenon: crowd sourcing – briefly put, the act of letting an undefined group of people contribute to a communal work of art where everyone works on an equal footing. Of course, the idea of abolishing the boundaries between artist and audience is not a new concept within the realm of art, but a new platform and technology for such endeavours has arisen: the Internet.

Within the context of art, then, the question facing us now is whether crowd surfing should be regarded as a genre or as an «anti-authoritarian» revolution? Does crowd sourcing herald the final «Death of the Author»? Or is it just a user-generated way of creating art that does away with any critical requirements about the quality of the end result because we can all join in anyway? Approximately one month ago the Copenhagen Art Fair offered a chance to see one of the first projects on Danish soil to address this complex issue in an inimitable, polemic way.

GESAMT

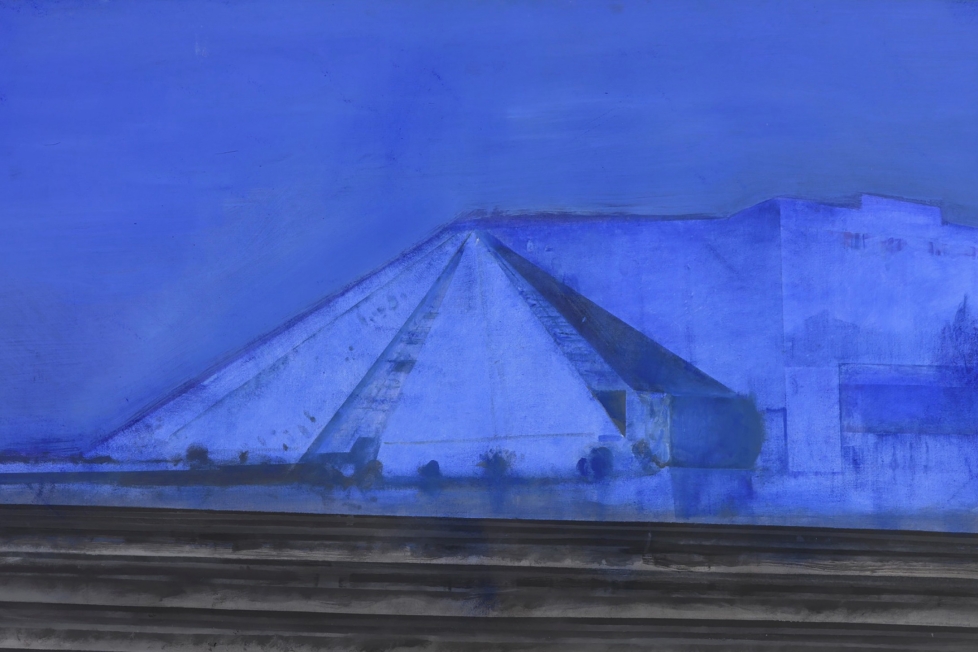

Lars von Trier, one of the last notorious auteurs in the world, was the instigator of a concept that revolved around inviting the entire world to contribute to a communal film piece: Everyone was welcome to submit their own footage and audio recordings. The recordings could have a duration of up to five minutes and should be inspired by quotes from six classic «masterpieces» chosen by Trier. This was no ironic gesture, but reflects how Trier often works himself: He will find a particularly noteworthy passage or point in an existing work and base his own work on that. The six works in question were Molly Bloom’s «Yes» monologue from James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922); a scene from August Strindberg’s The Father (1887); Albert Speer’s Zeppelin grandstand for the Nazi party rally (1934-37), Paul Gauguin’s self-proclaimed main work D’où Venons Nous? Que Somme Nous? Où Allons Nous from 1897, César Franck’s violin sonata in A minor (1886), and Sammy Davis Jr.’s satirical-equilibristic step act Choreography (1969).

Trier chose the title «Gesamt» for this «challenge», thereby immediately giving the entire concept juicy totalitarian overtones that went beyond any cautious democratic expectations about communication, audience involvement, and «community»; the very things that the Copenhagen Art Festival aimed for. The mere suspicion that the Chosen One would strike back against the masses also prompted several media to give free rein to the by now rather tired and worn-down cult of genius surrounding Trier. The effect may have been carefully calculated, even though Trier himself states that geniuses mainly belong in Donald Duck comics and that he himself has not regarded himself as a genius since late puberty. All that he did, really, was to whisper «together» in German. No promises were made of a Utopian-revolutionary Gesammtkunstwerk with a Wagnerian double-m and heiling valkyries as the world seemed to expect. Not even though the overall idea was to let works representing all the art forms come together, synthesising them in a single filmic work of art in a manner reminiscent of Wagner’s Hellenist dreams of having song, music, and drama – divided into «genres» by industrial specialisation – be reunited in a hitherto unseen monumental, socially and spiritually cleaning revolutionary form of opera.

But if Gesamt was not a totalitarian project and Trier is not a genius, then what is happening here? If you think about it a little, Trier’s talent is hardly a product of German theories about a Herrenfolk, but of a rather different political-aesthetic ideology known as «Good Taste». Trier grew up in a now-lost period of the history of the welfare state where it was still thought that thinking man should govern working man and where Brahmins of the Danish Cultural Radicalism movement successfully convinced the general population that an artistic intelligentsia – not economists, bankers, and politicians – would create the society of the future. It would appear that Trier still believes that great art generates more great art that can elevate an entire people. This is not about brainwashing, but rather about prompting us to move beyond parliamentary mediocrity and getting us to think for ourselves. We should not overlook the fact that modern marketing with its pandering to the notorious “lowest common denominator” is no less of a totalitarian idea than more overt forms of political propaganda.

- Gesamt. Disaster 501 – What Happened to Man?, 2012. Film still. Concept by Lars von Trier. Edited by Jenle Hallund.

Here, then, Gesamt does not mean «total», but together, in common. In fact, crowd sourcing really turns the entire idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk upside down. According to modernist mythmaking about the latter the masses do not create the Gesamtkunstwerk; rather, the masses are created through it. Crowd sourcing is about the opposite: it is about showing the masses as individuals.

DISASTER 501

Having launched Gesamt as a challenge for the crowd Trier then left the rest of the project in the hands of the young director Jenle Hallund. She was charged with the monumental task of selecting the best bits among the 501 contributions from all across the world, combining this selection to form a work that reflects her own vision. In just one month. It could all have gone horribly wrong, and indeed the whole thing had been disarmingly described as «an experiment». However, the project – which resulted in a four-track film entitled Disaster 501: What happened to man?, combining 142 out of the total of 501 contributions from 52 countries, shown simultaneously on four monitors – appears to have been in safe hands with her. She quite undoubtedly had the talent and fearlessness required to tackle so great a task.

As one sees the final result of Gesamt it might, however, appear that the relationship between the directors takes centre stage, overshadowing the people’s voice. Yes, Hallund has set out – as stated in the PR materials – to «honour the many emotions and moods» in the «touching» contributions received, but she has also ruthlessly smashed them and combined them to form something new. She states that for her, it was interesting that submitted materials mainly told stories about the decline in morals, about violence in the ever-lasting dance between the sexes, and about complex father-daughter relations. One really cannot help wonder whether this is actually Hallund’s own biased reading of the materials, seeing how they reflect her own struggle to measure up to a much-admired colleague, to seduce and dominate a man (and an audience), and simply make daddy happy. This should not be construed as patronising, nor is it pure speculation, for the issue is addressed throughout the film all the way to its epilogue. Hallund fearlessly let the film begin with a quite remarkable text about the relationship between the two directors as regards Trier’s canon of works.

One good thing about Hallund’s struggles with Trier is that they have imbued the film with tremendous energy and an idiosyncratic clarity that has, despite the great number of different contributions, prevented Disaster 501 from ending up as an insufferable cacophony of voices where everyone gets a say or as a piece of epigone, sinister Trier imitation. One is left behind with the impression that people are actually able to tell their own story and are not just keen to impress one of the greatest directors in the world. However, Hallund’s professional interests have a detrimental impact on other significant possibilities pertaining to the Gesamt idea. The weakest part of her film, Disaster 501, is undoubtedly the segment that addresses Albert Speer’s Nuremberg grandstand. It has become a predictable, distanced explosion of Nazi demonism, comedy, and nuclear bombs. Either this is due to the contributions themselves, or the director did not have the vision and overview to show us, once and for all, what makes Speer interesting apart from his own mythology and close relationship with the Führer. But of course Nazi aesthetics are interesting because monumentality and grand narratives are one of our greatest artistic (and political) taboos today. Our thinking is quite naturally affected by the creation of ever-more democratic and parliamentarian art that would rather paint people’s everyday lives up on the canvas than transcend those lives, elevating them to a very different scale so that art’s ideas and seductive qualities convey themselves to the audience.

Whether Disaster 501 is in fact as experimental as it is made out to be is difficult to determine. We can only conclude that crowd sourcing is not a particularly controversial method as such, but simply a contemporary art form that eliminates a number of conventions regarding the auteur, not always for the better. It is, however, rare to see the principle of crowd surfing reflected and brought to bear with such determination within the visual arts. That is why the Gesamt concept and Disaster 501 could have been the major highlight and attraction of the Copenhagen Art Festival. Especially if the project had been launched and presented a little better. On that score, however, the art scene is sadly sorely lagging behind the film industry.

SO WHAT?

It is less clear what Trier himself gets out of Gesamt. Perhaps he is making amends for the emotional manipulation he is always accused of subjecting his audiences to? To be fair, Trier has never hidden the fact that he manipulates people; rather, he has given people the opportunity to punish him by always foregrounding and exposing his own tricks. Now he even gives his audiences his basic recipe to see if they, too, can create good art with it. The gesture is both generous and perfidious – that is how «Good Taste» works. For preference, it is encircled by critical irony or teasing self-awareness, for the purely earnest and pathetic is fundamentally fascist in nature. Wit and self-criticism is what makes great art humanistic.

Some might regard crowd sourcing – or Wiki-art, as it is also known – as an outsourcing of the artist’s unique vision to a mass of amateurs, but this may not be Trier’s point. Rather, one person’s dumbing down may be another person’s invitation to greatness. There are even claims that participatory art makes people smarter because it is quite naturally driven more by concepts than craftsmanship, prompting it to speak more to our intellect. This may be absolute rubbish, but as a concept it could be regarded as a complicated counterattack against an anti-intellectual movement within arts and politics.

Whatever the case may be, other recent examples of user-generated art suggests that crowd sourcing requires a firm structure to prevent the results from becoming chaotic, mediocre, or trivial. Quite simply, crowd sourcing requires authorship in some form or another, even if that authorship is completely anonymous. This might place anti-authoritarian movements in a different light and prompt us to reconsider the relationship between copyright, copies, and imitation – and call to mind the old adage «Bad artists imitate, good artists steal.»

[FEATUREDVIDEO]