The discussion on quotas and affirmative action is raging in the art world. Michael Thouber, director of Kunsthal Charlottenborg, has relaunched the debate and made himself a champion of quotas after the publication of a survey (conducted by the editorial platform In Other Words and Artnet News) announcing that ninety-eight per cent of all auction sales in the world pertain to male artists, and that only eleven per cent of all acquisitions made by museums in the United States are works by female artists. For some reason, Thouber hit the mainstream media with his message. He was proclaimed a hero by no less a person than Ritt Bjerregaard, a former minister, EU commissioner, and mayor of Copenhagen, and a much-revered icon of women’s liberation since the 1970s.

The debate is far from new. It has been going on for decades, and not without yielding certain results – a fact that the Danish editor of Kunstkritikk, Pernille Albrethsen, has called attention to after having done a lot of counting. However, as someone who has worked for years and years on gender politics alongside fellow women and feminists, discussing affirmative action, quotas, and gender equality in the art world, I cannot help wonder why the message only gets heard this loud and clear when it’s a man doing the talking. Is it just about good communication skills, timing, and networking? Or is it about something else? The Other – for which we may read Woman?

In the early 1980s, British feminist art historian Griselda Pollock wrote an article called ‘Vision, Voice and Power: Feminist Art Histories and Marxism’. To summarise it very briefly, the piece is about art history writing in the 19th and 20th centuries: parallel with the establishment of civil society, women artists were essentially being written out of art history. Not that they had taken up a great deal of space or attention before, but even so a number of women artists dating back to the 18th century and earlier had practiced art very actively, almost on equal terms with men.

However, something happened in these formative years of art history. Men (for it was they who wrote the history of art) did not completely avoid writing about women, but greatly limited the extent of their writings; when they did write about them, they did so in rather negative terms, describing them as emphatically poorer artists than their male counterparts. Hand in hand with the invention of modern femininity (women are weak, not intellectual, destined to have babies and care for them, etc.), women artists were stigmatised as precisely that: women artists – a mark of poor quality in itself. Within art history, they were silenced by being stripped of their legitimacy, and slowly – quite slowly – it was not only the dead women artists who slipped out of art history: active, living artists of the time were not included at all, or were quickly forgotten. This is Feminist Art History 101.

But let us consider Griselda Pollock’s three chosen words: vision, voice, power. What is this all about within a feminist discourse? Vision is about seeing, as well as being looked at, meaning that it is about representation. Adopting an art historical perspective on the given period (the 19th and 20th centuries), we have looked at woman as the subject of art, not as the artist herself. Quite a lot of art has been made about this issue. Some of that art was created by the recently deceased American artist Carolee Schneemann, who spent her entire life as an artist working with the theme of being looked at (woman) versus being the one watching (man). She broke conventions by occupying both positions. Another American, the theorist Laura Mulvey, has described women’s cultural submission to the male privileged gaze as “to-be-looked-at-ness,” a term coined to describe a fundamental condition of women (including women artists) in a patriarchal culture.

But we all see and look, don’t we? Recently, the British theorist Sarah Ahmed gave a lecture in Malmö to mark her appointment as honorary doctor at Malmö University. She talked about white men being a system and a way of thinking, with special reference to the academic world. We need not limit this argument to academic life alone. It also holds true in the art world. It is a way of thinking that encompasses all of us because we cannot avoid submitting to this system that constantly reproduces its values. Similarly, art history and feminist theory have spoken of the white man’s gaze and voice to which we all subconsciously submit in the cultural exchanges arising in relationships. A gaze, and a voice, that assigns categories to us all in certain ways, and one to which we as women (regardless of ethnicity) also submit, performing ourselves in relation to that gaze in our own cultural actions. This is a gaze – a vision – and a voice that also grants power.

Speaking of quotas, gazes, visions, voices, and power in the art world – all the things that prompted this column – it is highly interesting to note that it is a man’s voice breaking down the media wall. However praiseworthy the results, this simple fact remains noteworthy because for over fifty years, many (especially women) have called attention to the skewed gender ratios in museums and in the art world. It all began back in the 1970s, and since the 1990s the issue has been consistently and systematically pointed out within the art world.

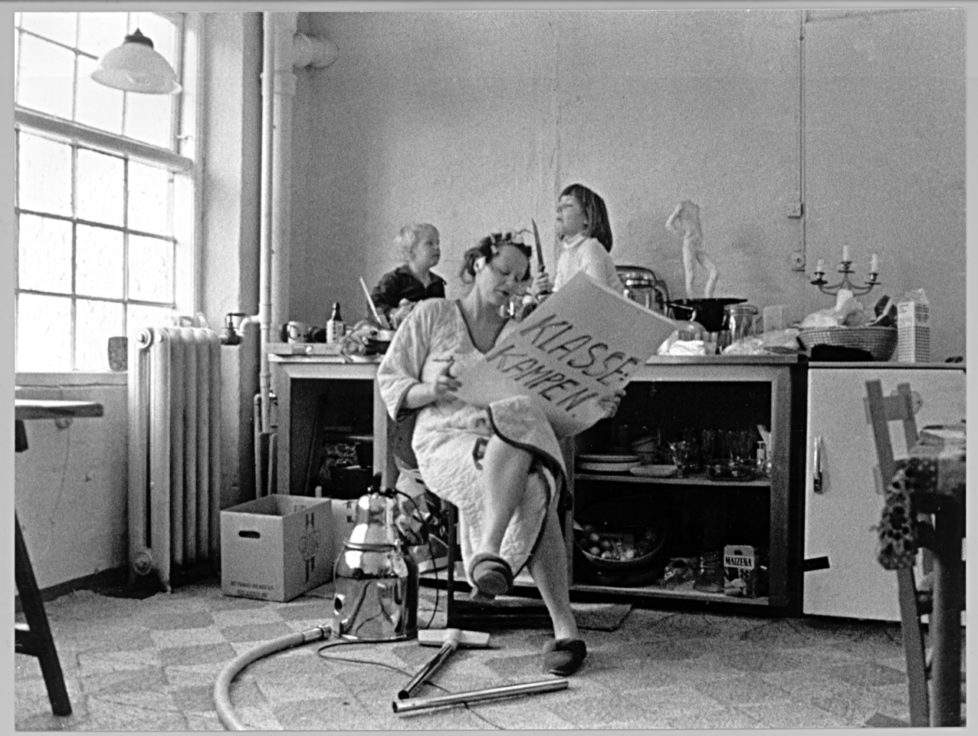

In 1994, Lene Burkard curated Dialog med det andet (Dialogue with the Other) at Kunsthallen Brandts in Odense, an exhibition which ushered in a new and reinvigorated discussion of gender issues on the Danish art scene. In 1997, artists Susan Hinnum, Malene Landgreen, and yours truly launched a digital publication, Inserts – 67 kvindelige kunstnere i Danmark (Inserts – 67 Women Artists in Denmark), which addressed discrimination against women artists on the art scene. The following year we arranged an exhibition on the same theme, Boomerang, at Kunsthallen Nikolaj in Copenhagen. The exhibition title referred to the fact that a boomerang always comes back if it fails to hit its intended target.

The year 1999 saw the publication of the first official report addressing the issue. It was published by what was then known as Museumsnævnet (The Museum Board) under the Danish Ministry of Culture (now the Danish Agency of Culture and Palaces). The report announced that just 6.5 per cent of all the artists featured in Danish museum collections were women. The figure included dead as well as living artists. In 2005, the same agency conducted a new survey, which showed that at seven selected museums, twenty per cent of the artists featured in the collections were women. In 2014, professor Hans Dam Christensen followed up on this study, and his investigations showed some progress.

The years between 1999 and 2014 featured a range of activities (see the list below) that discussed figures and gender equality in the art world. While these efforts generated some discussion at the time, they appear to have been quickly forgotten again. Still, they may have had some effect. The chosen examples are, in chronological order:

– Kvinder på Værtshus (Nynne Haugaard, Nanna Debois Buhl, Lisa Strømbeck, Åsa Sonjasdotter), Eds. Udsigt – feministiske strategier i dansk billedkunst [Outlook – Feminist Strategies in Danish Art], Copenhagen: Information, 2004.

– Dirckinck-Holmfeld, Katrine, and Honey Biba Beckerlee, Eds. At forhandle kønnet (Kunstakademiets 250 års jubilæum) [Negotiating Gender (on the occasion of the 250th anniversary of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts)], Copenhagen: Kunstakademiets Billedkunstskoler, 2004.

– Høyer Hansen, Lone, and Dorthe Jelstrup, Kirsten Justesen, Anita Jørgensen, Malene Landgreen, Lisa Rosenmeier, Katya Sander, Åsa Sonjasdotter, Elisabeth Toubro, Mai Misfeldt, Eds. Før usynligheden – om ligestilling i kunstverdenen [Before Invisibility Struck – On Equality in the Art World], Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 2005.

– Den Blinde Vinkel [Blind Spots] – Billedkunstneren no 1., 2007. A themed issue of the journal on equality in the art world in 2007, including figures on museum acquisitions. A conference on the subject was also held.

– Glahn, Charlotte, and Nina Marie Poulsen. 100 års øjeblikke – Kvindelige Kunstneres Samfund [100 Years of Moments – The Danish Women Artists’ Association KKS]. Højbjerg: Forlaget Saxo, 2014.

With just a few exceptions, all of these initiatives were launched and carried out by women artists.

So even though we are seeing progress in the figures for acquisitions at the museums, in the Danish Arts Foundation, and perhaps even in the media, we will probably still need to wait quite a few years before women are hailed as heroes for having raised their voices to discuss inequality in the art world. Apparently, the white man’s system still exists.

– Sanne Kofod Olsen holds an MA in art history. She is dean at Faculty Office for Fine and Applied Arts, University of Gothenburg.