After visiting Miriam Cahn’s exhibition at Kunsthal Charlottenborg, I wake up in the middle of the night, my head flashing with images. Coming from the world of dreams, where forms have soft contours that can quickly melt into their backgrounds, I turn on my computer and write the skeleton of this text.

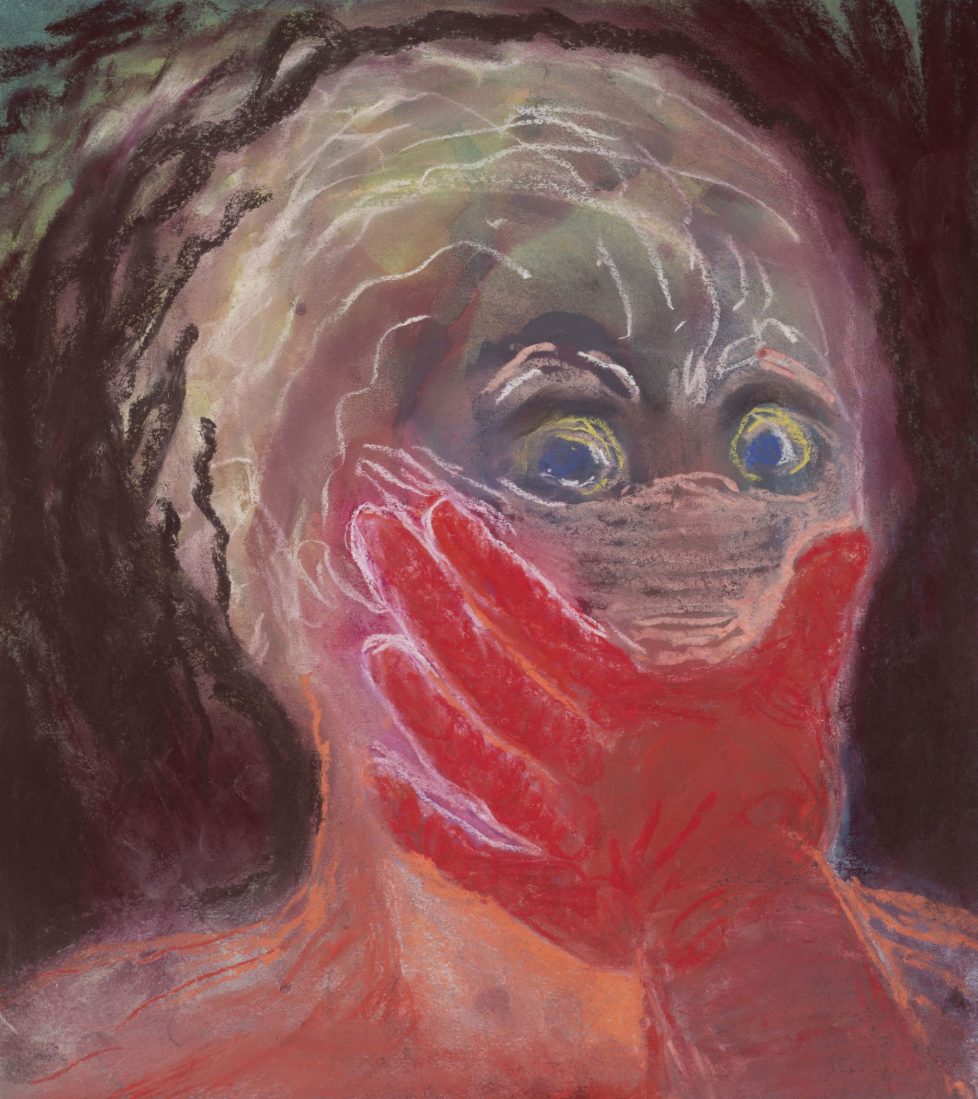

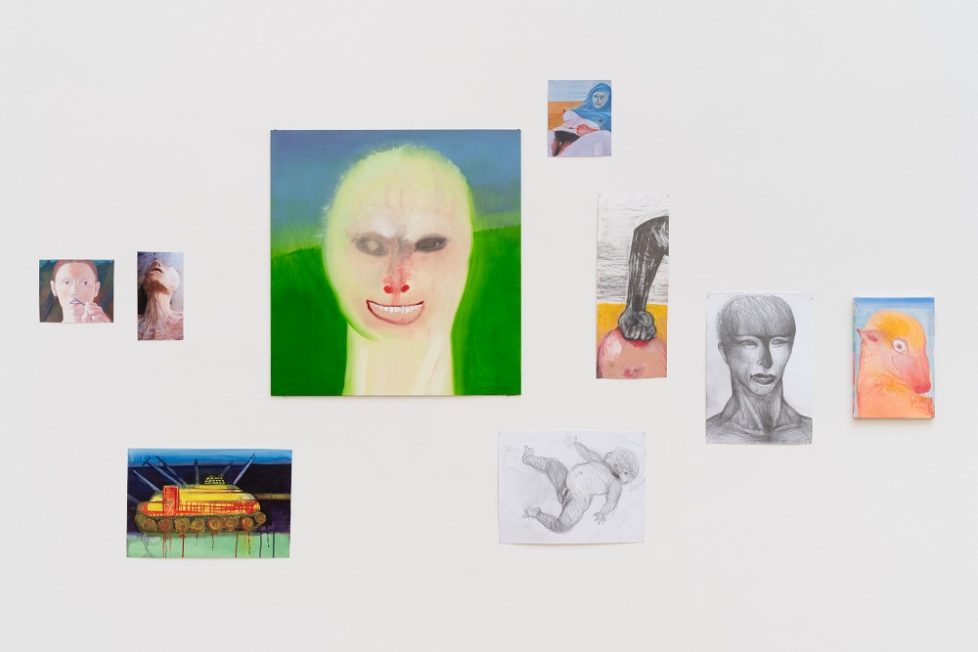

With darkness as a tricky accomplice, I obsess over the show’s multitude of unnerving images presented in colourful canvases, black-and-white drawings on paper, low-quality homemade photographic prints, all displayed un-hierarchically alongside each other. Bodies in glowing colours morph inside my head, all their orifices open. Eyes, mouths, vaginas, and anuses are sometimes filled with other (mostly male, it seems) flesh, and often stare widely out of the canvasses with terrifying looks.

Obsessing in particular over these holes, I have the feeling of being right inside someone’s optic nerve. And in the middle of the night, that nerve is a tunnel. It is a mysterious interior like the one depicted in Cahn’s painting of a burqa-veiled woman gently exposing her vagina’s dark hole with her fingers, in a mystifying invitation towards an internal space: überlebende (undarstellbar) (survivors [unrepresentable], 1998). In some other paintings, however, holes are not the openings of channels that connect bodily interiors and exteriors. When the bodies lose their mass and are flattened to two dimensions, their holes are no longer fleshy ties to an intimate inside – they are just circles on the round faces of cartoons.

This recurrent motif in Cahn’s oeuvre appears throughout the paintings in the first and second galleries, dedicated respectively to Europe’s migrant crisis and to sexual imagery. In the first gallery, adults and children, mostly naked and often protecting their genitals, are seen wandering in despair, their features stylised and partly two-dimensional. Penetrated by the paintings’ backgrounds, their eyes and mouths open into nothingness, making the figures look like ghosts. It is here that I realise, with perhaps more clarity than ever before, that the right to your own body means having control of your holes and what goes through them: speech, food, other people’s flesh, babies, and so on. Owning one’s holes is one of the basic prerequisites of being a person.

The lack of personhood in these bodies-without-real-holes is painfully amplified by the gestures Cahn uses to compose the image clusters displayed in this first room. Hanging alongside large brightly coloured canvasses depicting images of loss and anguish, are: a photo of a cat (lightly drawn upon and pinned to the wall); a picture of a pink flower; a painted sheep’s head staring at us weirdly; a small oil painting of a war tank; drawings of life-sized babies; vaginas giving birth; and it continues. The classic theme of war, which has always featured in Cahn’s work (including the nuclear threat, the first Gulf War, and the Bosnian War), is treated here with fierce anti-monumentality. Just so, it is from the almost playful choreography of this particular juxtaposition of images, that horror pours out.

Born in 1949 into a Jewish family that fled to Switzerland from France during the German occupation, Cahn has been closely touched by the drama of war and displacement. Since the beginning of her artistic career in the early 1970s, her work has been boldly invested in political issues and the feminist movement. Her outrage towards brutal power relations, abuse, and injustice summons these very realities in a dream-like system of déjà vu, repetitions, correspondences, and oddities. In doing so, she not only marks a space of artistic autonomy, but also demands that we accept that her pictures’ power lies in their being offers, possibilities, and configurations, rather than rigid representations.

Throughout the show, Cahn suggests that representation emerges not in the single image, but in the relation amongst images. Because of this inherent relationality, representation is a fluid constellation in flux, not only within the works themselves, but also in their connection to reality. In the text ‘torture pictures in may 2004’, which is exhibited as a series of A4 printouts pinned to one of the exhibition’s walls, Cahn reflects on how the outpouring of images from recent historical events can change, inform, and destroy art images, and vice versa. Have the snapshots of the female soldier nonchalantly walking a prisoner on a leash in Abu Ghraib forever changed the way we look at Valie Export’s 1968 feminist performance From the Portfolio of Doggedness, in which she walked her partner on a leash through the streets of Vienna? And has the terrorist attack on the Twin Towers altered how Cahn’s large drawings from the 1980s depicting the World Trade Center – which are also on display in the exhibition – are read and understood? Of course they have, because we cannot un-see.

Although these are timely and important concerns, and surely relevant for Cahn, I cannot believe that she accepts for a moment that today’s overload of “true images” can in fact- destroy what she calls “the aesthetic way of thinking.” In her ferocious defence of imagination as a dynamic process that connects images in complex webs of interpretation, representations dissolve into something larger and less palpable, but perhaps more powerful, than individual pictures. This is reflected in the composition of the exhibition itself: larger and more unstable than the images that make it up.

For a painting show, ME AS HAPPENING has an unusually performative power. For me, this is symbolised by a small oil painting, which is amongst the last ones displayed in the final gallery. It is a skillfully painted self-portrait of the artist as a young woman, her hand in the foreground in the act of painting. The same image is reproduced in the first gallery as a paper printout. I imagine this hand drawing a circle around the exhibition space, marking the territory in which things are “happening” according to Cahn. In this optic tunnel that I fell through while sleeping, she can explore themes classically associated with the male imagination – war, pornography, and capitalism – in her own, uncompromising and furious way. In this space, the world unfolds in, around, and through Miriam Cahn.

I think of her pictures as the afterimage fluttering on the back of the eyelids after staring intensely at something; it takes time for them to fade. Rocking myself back to sleep, I focus on the thirteen dazzling paintings of sleeping heads that compose the series Schlafen (Sleeping, 1997). Are they also dreaming of this show?